By C.R. Luismël

Santa Rosa del Yavarí, located in the province of Ramón Castilla, Loreto Region, is — and has always been — sovereign territory of the Republic of Peru.

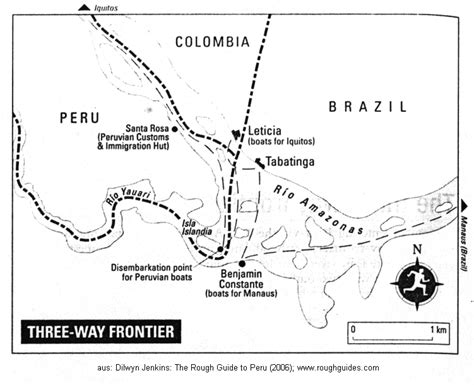

Far from being forgotten, the Peruvian State maintains permanent presence here through a local police post of the PNP, operating under high-risk conditions given its location at the tri-border area with Brazil and Colombia.

Santa Rosa and the Loreto Identity

For decades, traveling from Iquitos to the triple border has been a dream trip for locals — to Santa Rosa 🇵🇪, Tabatinga 🇧🇷, and Leticia 🇨🇴. These river cruises are as much about trade as about cultural exchange: leather shoes from Brazil, goiabada jam, fine coffee, and sweets from Colombia, even bottles of “Sangre de Boi” and Garoto chocolates.

This region — known as the “Amazon trapezoid” — was once a vital entrance for trade during the rubber boom. Machinery from Europe, Portuguese tiles, British preserves, and French goods flowed upstream to Iquitos, shaping a unique Amazonian modernity, despite the heat, isolation, and mosquitoes.

Why Is It Called Loreto, Not Amazonas?

Loreto is named after the Virgin of Loreto, patron saint of missionaries, especially the Jesuits who ventured into the Amazon. While it may seem the name “Amazonas” would fit, Peru chose “Loreto” precisely to distinguish its region from Brazilian and Colombian territories of the same name.

The Peruvian Amazon developed on a different path. Colonial authority was weak here. It was the Franciscans, Jesuits, and later Augustinians who made contact with native groups such as the Shipibo-Conibo, Boras, Witoto, and Matsés — each with their own language and rich traditions.

The Mistake of Lima’s Neglect

For decades, the Peruvian government failed to invest in or integrate the Amazon as decisively as Colombia and Brazil did. This allowed other nations to gain ground — often literally — while Loreto’s people, fiercely patriotic, stood ready to defend their homeland.

It wasn’t until the military and aviation arrived that change began. Peruvian pilot Alvariño was the first to fly over the jungle during the Putumayo conflict. Elmer Faucett, a U.S. citizen who chose to live in Peru, crossed the Andes by plane and landed in Iquitos in 1922, transforming connectivity forever.

Santa Rosa Today

Santa Rosa lies in the middle of the Yavarí river, a geostrategic yet vulnerable position. Unlike Leticia or Tabatinga, it lacks a proper airport. Its larger neighbor, Caballo Cocha (pop. ~10,000), supports tourism and resource extraction.

Santa Rosa thrives on cross-border trade and enjoys a duty-free status. Products brought here are tax-exempt if for local use, intended to offset weak private and public investment in the area.

The Forgotten Dream of Iquitos’ Independence

At different points in the 20th century, Loreto expressed aspirations for autonomy, even independence. These ideas faded after Ecuador’s 1995 attack during the Cenepa War. The attempted invasion reminded Loreto that it needed the Peruvian nation — and the nation needed to protect its Amazon.

The Acre Conflict

Acre, once part of Peru and Bolivia, became Brazilian due to occupation by rubber-seeking colonists, many of them descendants of “bandeirantes.” Brazil’s flat terrain and navigable rivers gave it a strategic edge. Peru, blocked by the Andes, could not assert effective control in time.

Leticia: A Painful Memory

Leticia was founded by Peruvians and considered Peruvian territory until the early 20th century. In 1932, a group of civilians and soldiers from Loreto reclaimed it, raising the Peruvian flag. Despite their success, the Peruvian government later agreed — through the Salomón-Lozano Treaty — to transfer Leticia to Colombia, hoping to secure diplomatic support in future territorial claims.

To Loreto’s people, this was a betrayal. They had won militarily, only to be overruled by distant diplomats. The sentiment of abandonment still lingers.

How Are Borders Drawn?

Historically, borders were based on rivers, hills, and visible landmarks — a system prone to future disputes. Today, rivers like the Yavarí and Putumayo have shifted course. Should we still follow those old lines?

It’s dangerous when modern politicians claim land based on river movements, especially when those claims are more political than legal. This may provoke instability in a region that has long-lived in peace.

Final Reflection

Santa Rosa is Peruvian — historically, legally, and emotionally.

Rather than sowing discord, neighboring governments should focus on developing the Amazon together. These communities deserve investment, education, health, and infrastructure — not political games.

The true challenge is not sovereignty, but solidarity in the heart of the Amazon.

C.R.Luismël

Aug. 6th 2025